If you believe that the outcome of this month’s elections could have changed anything fundamental about America, Christopher Hedges ’79, P’12 thinks you’re wrong.

If you believe that the outcome of this month’s elections could have changed anything fundamental about America, Christopher Hedges ’79, P’12 thinks you’re wrong.

As a journalist and writer, Hedges spent two decades living and working in war zones. He has seen combat in El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Colombia, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Sudan, Yemen, Algeria, Turkey, Iraq, Bosnia, and Kosovo. Retired from a long career as a war correspondent, he has turned his focus on a kind of domestic violence.

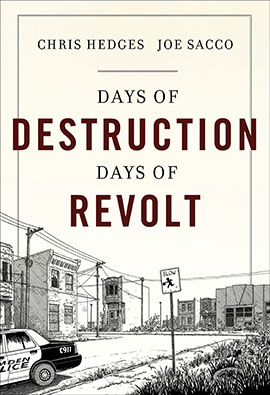

Hedges’ book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt tells the story of what he calls America’s sacrifice zones — locations where industry has destroyed the environment and ruined lives while harvesting the resources it needs to build profit.

Elected officials from both parties are either complicit or feckless, he asserts, and there is currently no popular movement that can stand in the way of powerful corporations.

For his book, Hedges selected several sites where the consequences of exploitation are in the highest relief — including Gary, W.Va., where coal companies use explosives to remove mountain peaks that separate miners from the seam.

After layers of earth have been blasted away, machines can easily scoop out coal, but the damage to the environment can be read in the scarred terrain, local cancer rates, and an alarming trend of climate change that scientists trace back to the burning of fossil fuels.

“There’s a kind of insanity to it where, as the planet begins to disintegrate, you use more violent methods to extract profit from it,” Hedges said when he visited campus October 22.

Astronomy professor Jeff Bary, who teaches Core Scientific Perspectives: Galileo, the Church, and the Scientific Endeavor, began reading Days of Destruction when he heard that it included a profile of Gary, just down the road from his home town of Welch, W. Va. When Bary saw Hedges’ description and correlated the coal industry’s condemnation of climate science with the Vatican’s treatment of Galileo, he knew that he had to bring the alumnus to campus to speak to students.

“It has a political bent to it that I hadn’t imagined for this class,” he said, “until I started to think hard about how the arguments I’ve seen trotted out — both for and against mountaintop removal — play into what I’m trying to get at in the Galileo course.”

Bary reached out to his colleague, anthropology professor Nancy Ries of the Peace and Conflict Studies Program, to cosponsor Hedges’ visit. “There’s an interesting parallel process that’s been happening in the PCON program,” Ries explained. “In recent years PCON has focused more attention on the conflicts inherent in resource and energy extraction, both locally and transnationally.”

During his talk in October, Hedges traced the political and corporate antecedents of America’s environmental crisis, then he talked about the present state of affairs and the future, should these shadows remain unaltered.

In addition to mountain top removal in West Virginia, he spoke about other “sacrifice zones,” like

South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, where he said the victims of America’s internal colonization have the second lowest life expectancy in the western hemisphere — just 47 years for males. And Camden, N.J., once the home of RCA and Campbell Soup Co., which is being recycled from the inside out — barges stand ready to take scrap metal, gutted from the city’s dilapidated buildings, to China and India.

“I wanted to go into these sacrifice zones,” Hedges said, “because what happens to them becomes the template for what’s going to happen to the rest of us.” The only answer Hedges can see is massive civil disobedience. Today’s elections are not going to change anything; the people must pour into the streets.